Zombie Nationalism

Hollow institutions and the ultimate sacrifice

It worked!

Morning all, from my book-writing bunker. I’ve done my first three chapters! To my joy and relief the mini-sabbatical worked, so herewith normal service resumes for another stretch, while I brew the next three chapters. I’m so grateful to those of you who have stuck with me during this few weeks: your support really is the 21st century equivalent of a writer’s advance, and I appreciate every one of you.

Post-National Warmongering

For now, a note on a strange and unsettling media moment this week. In the last few days, both NATO chiefs and high-ups in the British Army have warned that Europe must prepare for war. Meanwhile the people who’d actually be doing the mobilising have responded, for the most part, with scorn and indifference.

From the perspective of these institutions themselves, the prospect of war may actually feel pretty real. All the signs point to Trump being serious about withdrawing the US security umbrella partly or even entirely from Europe, a situation that has simply never obtained in my lifetime - or indeed in the lifetimes of pretty much anyone alive today. And yet a US Representative, Thomas Massie, introduced a Bill just a few days ago, proposing US exit from NATO.

For European panjandrums, this is a real record scratch moment. Fully off the reservation. There’s pretty much no one alive now in either Western Europe or America, old enough to remember when our continent wasn’t an American protectorate. And now, having lost almost all the muscle memory needed for military sovereignty and decision-making, suddenly European leaders are facing the prospect of a not particularly friendly Putin to the East, and no Uncle Sam with a big stick in the background.

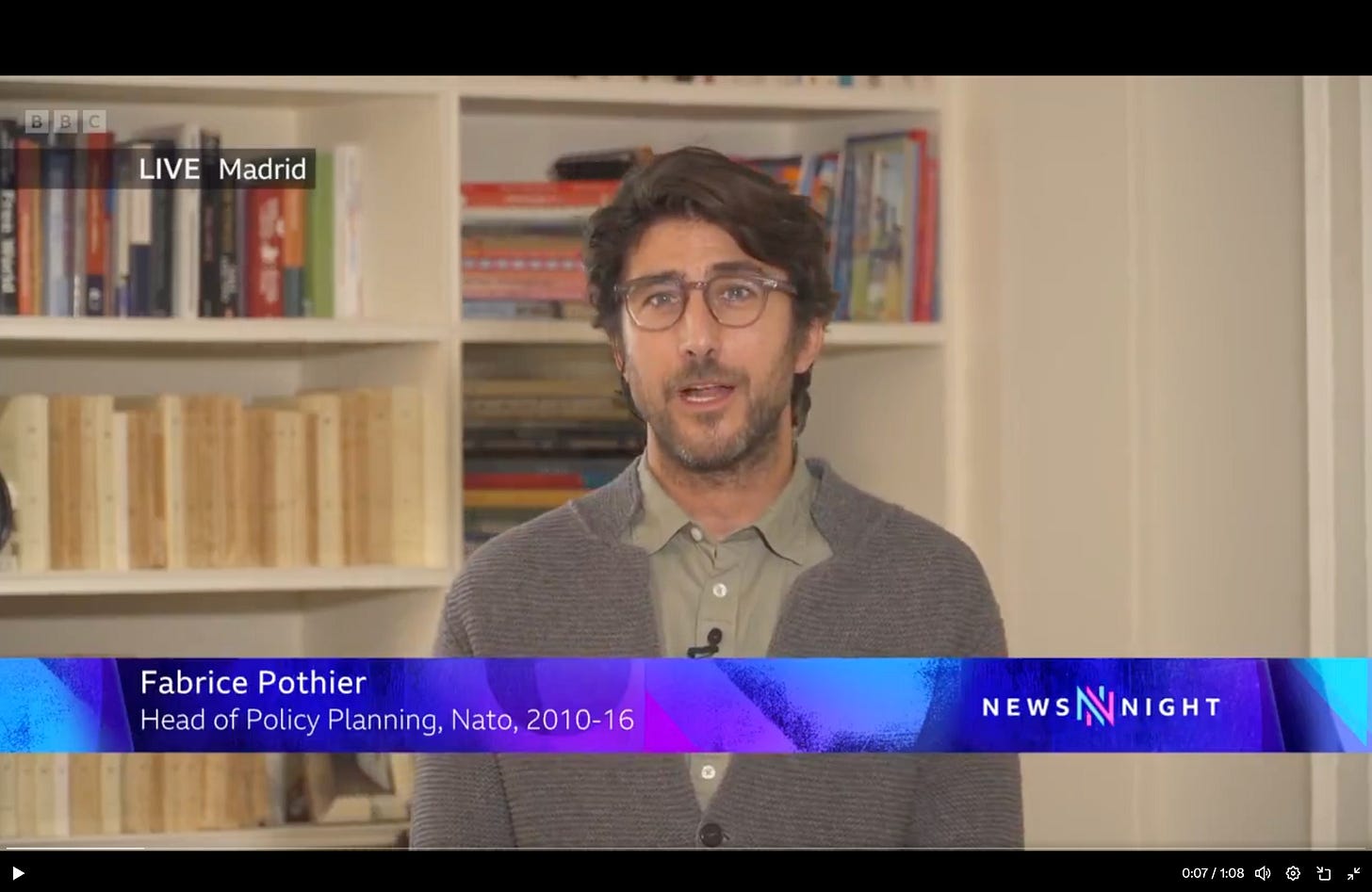

Now what? Prepare for what kind of war? How, exactly? Some cardigan-wearing ex-NATO guy made Churchillian references about “Europe’s finest hour”. But he, like so many other institution-dwellers, seems oblivious to the total disappearance across Europe of the social and material context within which that kind of war occurred, was publicly embraced, or even physically possible: widespread European industrial capacity.

This wasn’t just material infrastructure but cultures, skillsets, and social norms. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the countries of Western Europe were full of factories that could be, with relatively little effort, turned over to making munitions. These countries were also full of people who were familiar with this kind of work and able to contribute usefully to it. And - importantly - they were, by and large, socially cohesive enough to be willing to undertake it.

All of these things have also arguably largely disappeared in the USA. All the Western countries have methodically de-industrialised over recent decades, whether at the behest of financial capital, globalisation, or assorted ideologies of climate, diversity, and so on. They have, as a result, shattered the economic sovereignty, social cohesion, and industrial capacity that would enable the kind of large-scale mobilisation which occurred in the first and second World Wars. When this was effected, it was considered a feature, not a bug; it’s possible some are now wondering if this was really true.

But in any case, the USA isn’t the one now making belligerent noises at Russia, based on I’m honestly not sure what beliefs (or maybe delusions) about the continent’s capacity to follow through militarily. Lest you mistake me, I’m not saying “Europe has fallen” or any of these stupid internet tropes. People here can still get their act together, when they want to. This remains a wealthy continent, where (compared to many other places) things still work pretty well. The question is: on what basis do people get their act together, for whom, and against whom?

Just yesterday I received in the post a classic text: Historical Evolution of Modern Nationalism, published 1931 by then Professor of History at Columbia University, Carlton J Hayes. It’s an odd read: so Whiggish in places that I have to “hear” the text in the clipped accent of a 1950s American documentary or it feels laden with irony. But it’s valuable for having been written both from outside Europe, and also between the wars, before the post-Hitler consensus solidified the conviction that “nationalism” on the modern European model was axiomatically bad. Hayes is more ambivalent, and hence willing to trace the history of this worldview without the modern-day need to lard it with health warnings.

I’m only a few chapters in, but one of his eary points is that “nationalism” in what was to Hayes the modern sense, and which to us now is an historical artefact that peaked with the two World Wars, didn’t really come into being until the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Conflict between “states”, prior to this, really meant conflict between ruling aristocracies. Ordinary people were, for the most part, not much involved in the fighting; as Hayes sees it “European peoples were bartered from one reigning family to another like so many cattle, sometimes as a marriage-dowry, sometimes as the booty of conquest.” The same went, he says, for the populations of overseas colonies.

The nations that arose from the seventeenth century on were different. They generally weren’t ethnically homogeneous, unless you consider all European peoples to be the same ethnicity (which only makes sense from an American or Third Worldist perspective). Rather, they typically had one dominant, “official” people and language, but also absorbed a cluster of other peoples and dialects, making them “more akin to small empires than large tribes”.

What constituted these “nation states” as such was a sense of self-consciousness as nation-states on this new model: one that, as Marshall McLuhan argued in The Gutenberg Galaxy, couldn’t have emerged without mediation by print, and the linguistic consolidation and growing national self-consciousness print literacy enabled among those polities where it spread. Nationalism was, McLuhan points out, an upper-class ideology before it spread to ordinary people, tracking the propagation of literacy from the top down. It was in this context that the characteristic modern “nation state” was able to emerge: one in which a linguistic and cultural cluster was mapped to a geographic area, industrial economy, and political regime, all held together by a print-mediated collective sense of itself as what Benedict Anderson called an “imagined community”.

Now, the problem for ruling elites today - especially in Europe - is that this model really doesn’t apply any more, for several reasons. For one thing, print has now been superseded, not just once but several times: first by Radio, then by TV, and now by the internet. In that context, it simply isn’t possible to generate a nationalistic filter bubble in the same way, any more. Think of it like this: in the 19th century, when the only available mass media were in print form, the extent of what we’d now call a “filter bubble” was newspapers and other publications physically available in your area, in your own language. Inevitably, that created a self-reinforcing common sense of shared reality that mapped approximately to your geography, linguistic community, and hence - by a circular process of reinforcement - in time to your nation-state.

This was relatively straightforward in the British Isles, where the border is clearly defined by ocean; it was a bit more complicated in Europe, where distinct linguistic communities were often very interleaved, and this is part of what precipitated the World Wars. But with the advent of electronic mass media, first in radio and TV and now with the internet, the model grew basically defunct.

Today people still have filter bubbles. But whereas “nation state” filter bubbles had a material component, limited by the circulation of physical printed media, the new kind have come almost completely unmoored from physical geography. Instead, they’re bounded by linguistic communities. I don’t spend much time on Chinese or Hungarian social media; by contrast, regardless of geography the Anglophone filter bubble is all now functionally the same place, even where considered from a realist perspective the political interests of its geographic participants (for example Brits, Kiwis, Canucks and Americans) are often quite divergent.

There are countless examples of this, but the most salient for our subject here is surely the geopolitical threat posed by Russia.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mary Harrington to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.