The Only Cure For Internet Poisoning

Preliminary notes on RAM, ROM, and κηρινὸν ἐκμαγεῖον

Apologies for the lateness of this week’s message. Several things conspired: firstly, I was SO CLOSE on Friday to finishing a chapter that I decided it was better to press on, with the ideas fresh in my mind. Lo and behold: the fourth chapter is finished! This means I have now drafted the introduction and also part 1, which lays the historical and theoretical groundwork for the rest. Words can’t easily convey how elated I am.

Secondly: we have a poorly chicken. I wouldn’t normally mention so domestic a matter, but the ailing hen is Minty, who featured in a previous post about “grindset” and the Thomist idea of “mastering our natural bent”.

She’s warm, comfortable and well-supplied with food, and seems a bit more perky today. We hope she just has a bad cold and will pull through. But please spare a warm thought in passing for the recovery of Minty the hen, who truly has mastered the art of fully being her creaturely self.

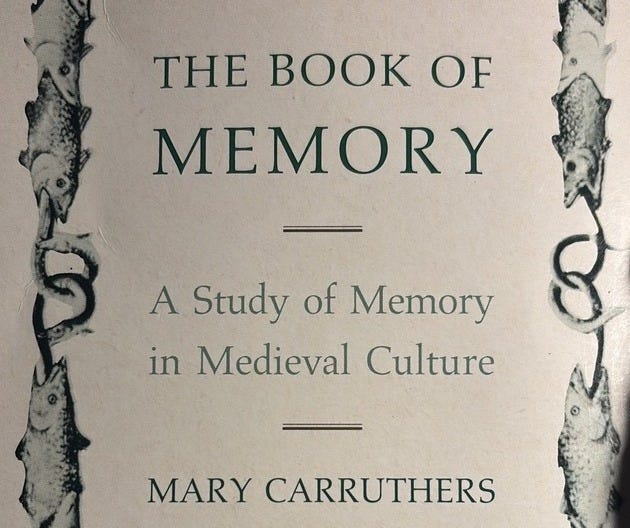

Finally, this week’s topic is my HUGE excitement on opening a text recently recommended me, by a scholarly friend who has read parts of my book in draft:

I’m only into the foothills of this fascinating text, but in brief it’s a study of medieval theories of the theory, function, role, and cultivation of memory in the culture that preceded the printing press. That is: manuscript culture, an age in which books were rare treasures, laboriously produced, and so precious and vulnerable they were often collected in walled libraries, chained to desks, or even locked in chests.

Under such circumstances books weren’t ready to hand most of the time, as they are now, so an elaborate theory and practice of memory flourished. This theory and practice distinguished between the how of remembering (mnemonic schemes, which Carruthers calls “heuristic”), and what is remembered, plus a subtle phenomenology covering the experience of remembering, and the relation between a memory and what is remembered.My friend recommended me the book in relation to my chapter on manuscript culture, but my immediate thought on opening Carruthers is that its relevance is far more contemporary.

One of the phrases I have been kicking around lately is “The Great Forgetting”: a hunch that in embracing AI, as an extension both of our capacity to remember and of our heuristic faculties in retrieving and arranging what is remembered, we run the risk of allowing faculties to wither that are in fact central to our capacity to think. (I made this case, and also that it is unevenly distributed across social classes, recently in the New York Times.) Building on these themes, my working hypothesis is that at least at the collective level AI is survivable, but only provided we counterbalance this effect by deliberately cultivating our human faculty for memory, as distinct from the digital kind.

Carruthers cites Plato, who describes this human faculty as “κηρινὸν ἐκμαγεῖον”, resembling a block of wax in which impressions are made, held, and can be over-written. It’s surely true that every age draws analogies between human cognition and familiar modes of information storage and retrieval: in our case, computers, and in Plato’s, wax tablets. But I think there’s something hugely important about how tactile as well as visual Plato’s analogy is, in eloquent contrast to the mute abstraction and human-level illegibility of the digital one.

I don’t use wax tablets for storage, but Plato’s analogy still feels metaphorically far closer to how I experience remembering than the analogy from computer memory. Memorising a form of words or succession of ideas for repeated reflection produces an inner experience that feels, to me, like something I can both see and touch, and around which other ideas then cluster and crystallise. I often compose essays and arguments when out dog-walking or running, and can later recall whole sequences of ideas by picturing where I was when the thoughts came to mind.

It seems intuitively right that being deliberate about how we cultivate this inner landscape would in turn, form our overall patterns of thought. AI, though, incentivises the exact opposite, in the now-normative student practice of giving your homework to Chat-GPT. Meanwhile, if using Chat-GPT effectively bypasses inner formation, doomscrolling is instead the polar opposite of deliberately shaping the inner wax tablet. When we doomscroll, the experience is of accumulating others’ short-form thoughts seemingly at random, out of a torrent of such thoughts (and never mind how algorithmically conditioned the torrent is overall) then allowing the resulting patterns to form our inner landscape.

Where memorisation and meditation is intentional, this is passive. But the resulting patterns nonetheless shape the inner “wax tablet” of thought and memory, and hence also the ideas that are subsequently able to crystallise. This on its own could perhaps help explain something I’ve recently learned: that the only reliable antidote to internet poisoning, the feeling of inner unease produced by too much doomscrolling, is prayer.

This probably needs elaboration at greater length, in a separate essay; time is short today, so I’ll stick a pin it for now. There’s so much more to say on practices of memory in relation to the digital memeplex. I expect to revisit this as I get deeper into the Carruthers book and into my own book draft. But let me know in the comments if you too have a practice for countering internet poisoning, or for cultivating your non-digital, human, “wax tablet” capacity to memorise, recall, and re-compose. As we all slip deeper into this post-print age, I’m coming to think our best hope of cultural survival lies in rediscovering and re-applying the ancient ars memoriae.

Yes to all of this. My antidotes to internet poisoning are prayer and Mass. Attending Mass every week, sometimes twice, is the most cultural thing I do. The music, incense, art, prayer, and community are profound balm for any anxiety. I also pray every morning. Lastly, I read old books and realize we're all grappling with the same stuff age after age. Another book you might check out on memory is St. Augustine's Confessions. Lots to say about memory in books teen and eleven and lots to say about truth and understanding differences of memory and truth in book twelve.

For me. the first inkling me that computers might be causing our mental faculties to atrophy came with the introduction of the GPS. Until then, we we all largely obliged, with the aid of printed maps, to form a mental chart before settling out on a journey, which we did with varying degree of success, only occasionally having to stop and ask a local for directions (with the concomitant wound to masculine pride, but I digress). I wonder who does that now, and wonder even more if anyone who grew up with GPS would be able to get around without it...

As for AI and memory. I feel this less acutely, than the effect of GPS and our sense of direction. This might be simply due to it's relatively novelty, but as yet I don't feel abilty to lay down memories and retrieve them has been seriously impacted. Without a doubt though, internet scrolling does have as adverse effect on one's attention span and patience with more long form media. The only remedy I've found so far is to "go dry" on social for a period of weeks and months - it does help restore some sort of balance. I suppose ideally we should cut ourselves off altogether, but very few are prepared to go truly off grid, with all that entails.

I do think we might be forced to one day through. As I'm sure a lot of people are aware, Frank Herbert's "Dune" saga is premised on a future civilization where AI, or "thinking machines" are outlawed following the "Butlerian Jihad", and where complex mental tasks are performed by rigorously schooled humans. It seemed outlandish, even back in the 80s when I first came across it. It seems far less so now.