Heritage, Death, and the Gen Z Right

The tragic old age of post-war progressivism

Last weekend I flew from London to Delaware to eat BBQ, and it was totally worth it.

I was a guest at a roundtable discussion hosted by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, for their annual Homecoming event, in the Brandywine valley near Wilmington, DE. That’s a long way to travel for just 36 hours, and I’ve been a bit tired this week, but I came away so energised by everyone I met there I haven’t minded at all.

This isn’t just because I love BBQ, a cuisine that is for some reason quite difficult to find outside the USA. It’s also because ISI convenes young people from colleges all across America, with an interest in the Western intellectual tradition, who are without fail serious, well-read, and whip-smart; a few hours in their company was immensely cheering.

But their mood of energy, purpose, and moral seriousness stood in curious contrast to little group of protesters, that gathered outside the Wilmington hotel where I and the other roundtable guests from out of town were accommodated. There were maybe five or ten of them, waving signs that warned of dire things like “Nazis”, and “Dictatorship”. Aside from the fact that this seemed a slightly overheated response to a student society for the study of great books, what struck me was their age. I didn’t take photos, as doing so seemed needlessly provocative, but as a group they looked of about the right vintage to have come out in protest at the politics of their parents’ generation, during the Vietnam War. And now, here they were, waving placards again at the politics of their children’s generation too.

I think they were mostly there for my fellow-panellist Kevin Roberts, who is President of the Heritage Foundation. The proximate driver was likely Heritage’s sponsorship of the “Project 2025” policy programme, which has played (to say the least) a controversial role to date in Trump’s second term. But their enemy is surely also Heritage in a more allegorical sense: this style of postwar protest stems, at root, from a kind of permanent revolt against the idea of inheritance or legacy as such - and hence also against time, and death, and the possibility of history.

We all grow up shaped by the ambient assumptions of our youth. I was a teenager during the End of History this generation briefly conjured into existence. Then, as a twenty-something, I witnessed its end; that has formed me. But I often wonder what formed this generation in particular, such that perpetual revolution against what comes to us from the past came to seem not just possible but desirable. Not all boomers, obviously; but the revolutionary subset cannot be denied. I imagine the answer to “why” would fill books. And today we all live (ironically) with the anti-heritage these post-war anti-heritage progressives bequeathed us.

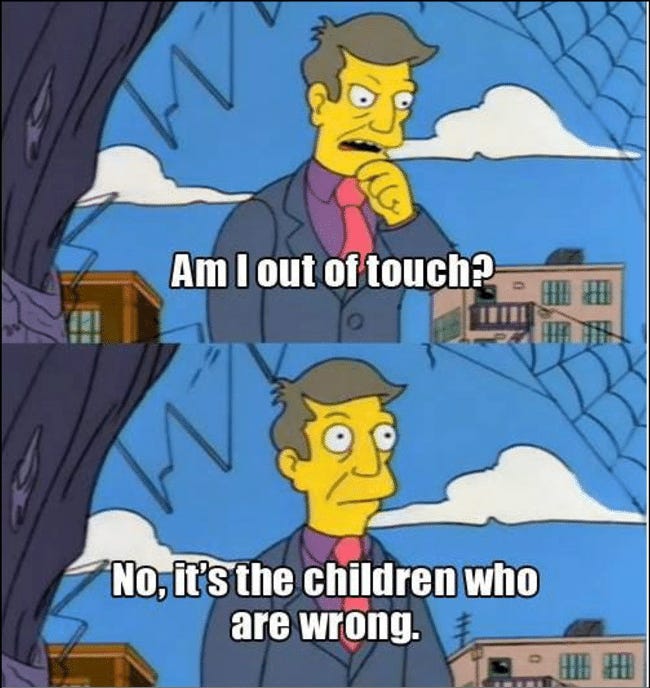

Meanwhile though they’re not as young as they were , they’re still turning out on the streets, for literal anti-Heritage protests. And there is something especially tragic about the collision between this mindset and the passage of time - not least in that a subset of the youth is now rebelling in turn, against their anti-legacy of negation.

This includes the young people whose event they had chosen to picket: a group that could not have been further from dispositionally hostile to heritage. The ISI kids came across to me as serious and literate, exuding an optimism that felt both youthful and in communion with the past. Some of them had brought their own future, too: babies and little children, who cooed or played in the grass as their parents mingled. By contrast, the visibly-ageing Awkward Squad outside the hotel seemed to have no younger members, no successors: a youth culture trapped in futile and increasingly tragic mutiny against time itself.

This sense of a tragic dénouement now unfolding in post-war progressivism came back to mind once more, after my return to England, as I read a New York Times interview with the children’s author Robert Munsch. Munsch is the author of many well-known children’s books, of which one of the most famous, Love You Forever, is a poignant depiction of the cyclical continuity of human love, over generations of birth, life, and death, that seemed to me warmly embodied by those young, bookish ISI parents and their accompanying families. In it, a mother sings this lullaby to her baby:

“I’ll love you forever,

I’ll like you for always,

as long as I’m living,

my baby you’ll be.”

She continues to sing it to him as he grows up. Then, as she herself grows old and frail, and her death approaches, her now-adult son cradles her in his own arms, and sings the lullaby to her, swapping “baby” for “mommy”. Later he returns home, to sing the same lullaby to his own baby daughter.

Nothing could more movingly capture that heritage of love that families hand on down the generations: a heritage more fundamental even than any literary one of books or ideas. The story grows more poignant when we learn that it was inspired by Munsch’s own grief at the stillbirth of his two children (he later raised three adopted children). But what finished me off was learning that Munsch, now 80 and living in Canada with dementia, has requested, and been approved for, Canada’s doctor-assisted suicide programme: MAID.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mary Harrington to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.