Beware of Lords and Princes?

Public intellectuals, integrity, and aristocratic patronage

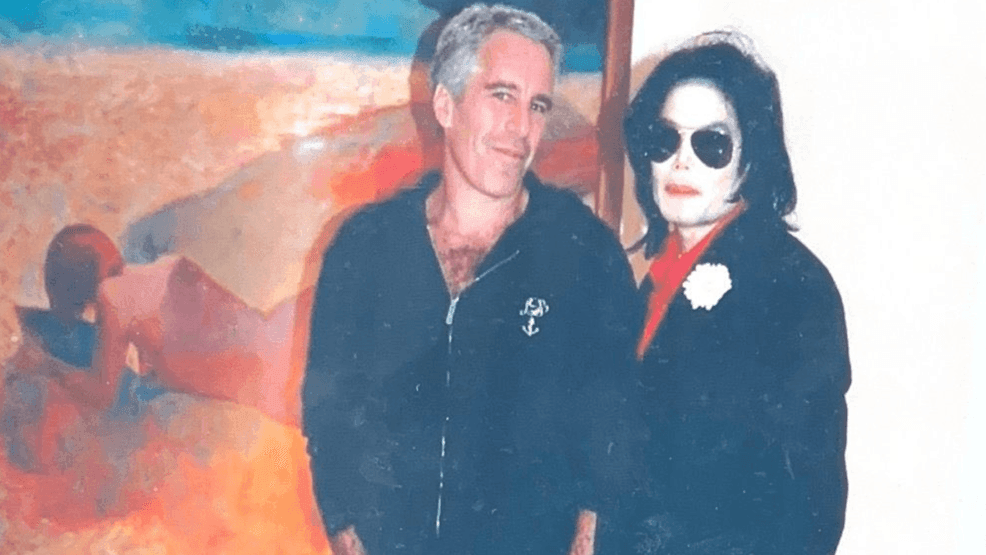

Toward the end of this last week of Epstein pandemonium, in yesterday’s FT Janan Ganesh put his finger on a key aspect of the operation: the way this man acted as broker between the financial one percent and what Ganesh calls “the public one percent” - a group with clout but not necessarily so much money:

Artists, intellectuals, politicians, even the occasional journalist: the public rather than private 1 per cent. Their value in social settings is high. Their income might not be. It is hard to get rich doing something fun. Again, most of them just shrug this off as the tax on having a cool job.

What struck me here was the way Ganesh’s description meshes with something I’ve been tracking for a while: the re-emergence of aristocratic patronage, for culture-makers. As Ganesh notes, the wealth gap between apex financiers and apex culture-markers creates a world of temptation:

Even those who really mind will often find a clean solution, such as the classic private-public intermarriage, where one spouse provides the wealth and the other the social clout. (George Washington’s marriage to a Virginia plantation-owner is a template from the annals of hypergamy.) A few, however, will do improper things for the rich to get some of their crumbs. It is just too jarring for them to be the star of a dinner party and then fly economy.

Is this always, or only, a recipe for corruption? It’s complicated. The picture Ganesh paints bears comparison to the aristocratic patronage arrangements that were common in the Middle Ages. If you spend any time at all rummaging around in the literature and history of the past, several things become clear. One: there has always been a small subset of people who form a “Public One Percent”: perhaps not identical to today’s celebrity culture entertainers, but who stand head and shoulders above others in their field, and who tend to seek one another out internationally, more or less regardless of age, sex, faith, or other identity markers, for the exchange of ideas. Two: those people historically tended to wind up with aristocratic patrons.

Back then, copyright wasn’t a thing, and nor was mass-producing your works and earning royalties. Instead, intellectuals generally sought the protection of lords and princes, who would bankroll their existence in exchange for the clout that came from having leading intellectuals floating about their entourage. If that sounds a bit like what was happening when Epstein collected novelists, filmmakers and models as dinner guests for his dorky billionaire clients, that’s because it was.

But does that make it corrupt by definition? From the idealistic, “speaking truth to power” vantage-point we tend to associate with modern artists and writers it looks dodgy in the extreme, pretty much by definition. But is it completely indefensible? Really, it probably depended firstly on your patron, and secondly on the work your patron wanted to commission. In the16th century, for example, the Renaissance Italian esotericist Pico della Mirandola spent much of his (relatively short) life in the orbit and protection of the Italian statesman and patron of the arts, Lorenzo de’Medici. Medici also supported some of the greatest Renaissance artists, such as Michelangelo and Botticelli. In the 17th century Cosimo, another Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, would act as patron to Galileo Galilei.

From the age of print onward, though, public intellectuals were increasingly able to make money directly rather than depending on patrons. If Galileo had a lordly patron in the 17th century, by the 18th the English poet Alexander Pope was able to make so much money just from his translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey he could buy a villa in Twickenham and set himself up as a gentleman. Print publishing was efficient and cheap enough, readers sufficiently numerous, and the legal environment sufficiently well-developed, that for two centuries after Pope writers were able to make a living more or less directly from paying audiences. That, then, becomes the basic economic condition wherein writers begin to imagine themselves “speaking truth to power”.

By and large, though, it doesn’t work like that any more. There are outliers, such as JK Rowling, but for the most part it’s no longer possible to make a living directly from book publishing. The chief culprit is the internet, which has the liberating power of loosening constraints on who can write, but with the concomitant effect of diluting formerly reliable writerly income streams away.

It remains possible to make a living as a public intellectual, but the ecology now works very differently. For one thing, as Rob Henderson has recently observed, there’s a convergence afoot between what writers do, and what influencers do; to succeed as the former you need a multi-channel presence more like that of the latter, and you have to keep plugging away at it. And not everyone enjoys this, or is good at it, or can command a big enough audience to make it work. For these, the best realistic alternative really is aristocratic patronage of some kind.

For this group, there are surely lessons in the Epstein debacle.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mary Harrington to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.